Book Review | Fatal Discord3/31/2024

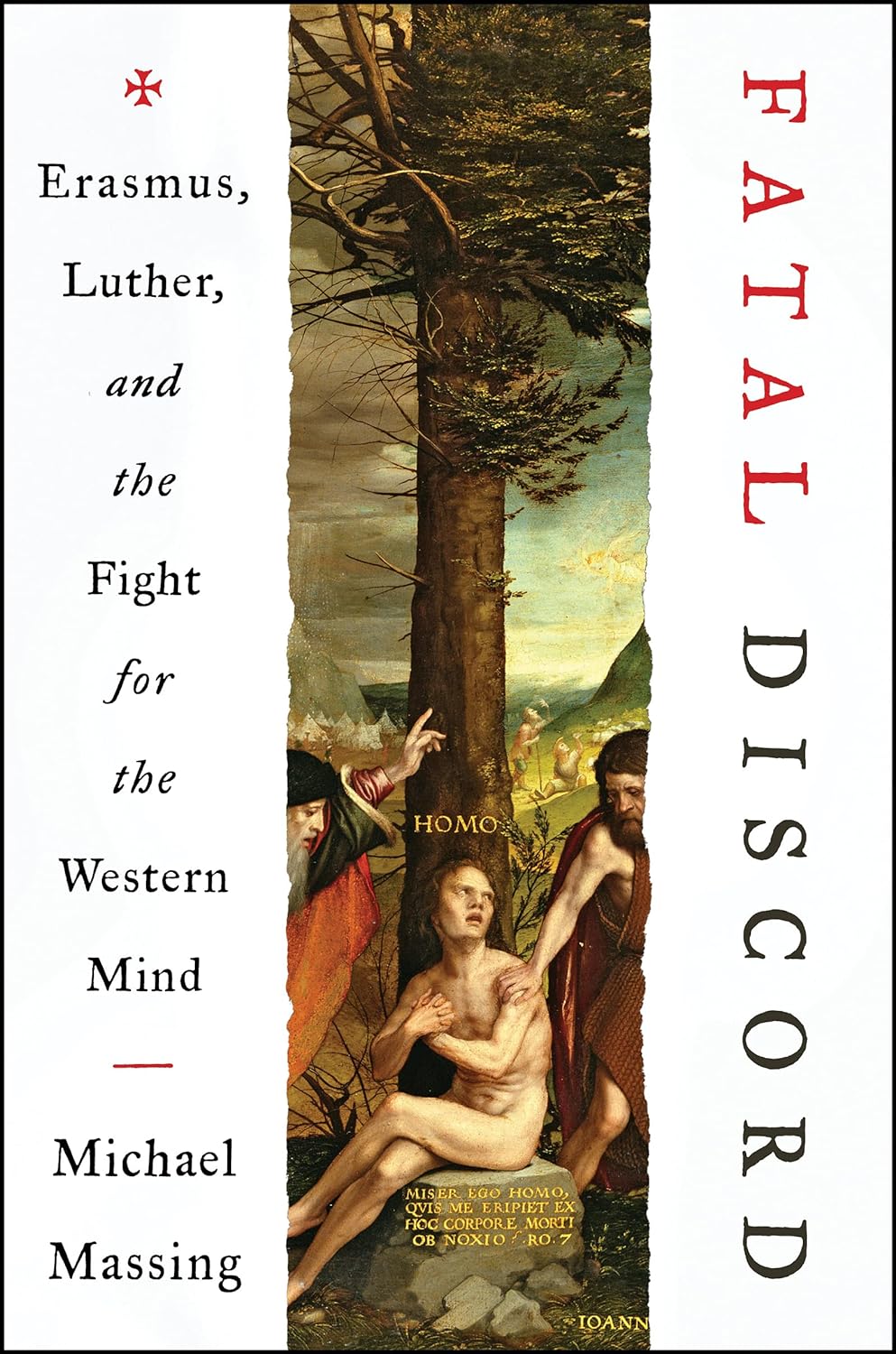

Hatching an egg, Another laid Fatal Discord, Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western World. | Michael Massing, HarperOne (2018) 1008p. Dense, yes. Hefty, absolutely. However, neither of these qualities should be off-putting to those curious about the world we inhabit. This is not a tome merely for the academically inclined; it is much more relevant to today’s current events than its subject matter unsuspectingly suggests. To reach this relevance, the reader must slog through amazingly detailed accounts of obscure internecine battles and absorb precise delineations of a distant time. While this context density extends the journey, its travelers are provided an understanding previously only available to those with advanced medieval studies. The author's central thesis is that the break with the medieval world, which birthed the modern, is the fault line of disagreement between Martin Luther and Desiderius Erasmus. This intensely pitched divide ultimately unfolds as the division between what we now recognize as Christian humanism and Christian evangelism. The first half of Massing’s work is a straightforward dueling biography. The careful documentation of events in each subject’s life and exacting place-setting is what one can expect from an award-winning journalist like its author. Massing, a Baltimore native, is the former executive editor of the Columbia Journalism Review. While academically accomplished and professionally prolific, this is his first book, and its topic is outside the scope of his daily practice. Regardless of where one sits in the stadium—on the side of Luther or Erasmus—the first hundred pages are informative and neutral in their presentation—again, very journalistic. It is not until both men’s careers are in full bloom that one starts to see—as would be expected—a basis for the modern reader, as their previously rooted positions take firm hold and are judged by today’s perspective. In Massing’s telling, Luther is an intolerant fundamentalist focused on theological purity over peace. Erasmus’ faith emphasized the primacy of harmony and goodwill, which we call humanism today. Both men were virulently anti-Semitic. Additionally, both thinkers sought, at least initially, reforms in both the practice and doctrines of the then-prevailing Roman Catholic Church. Luther went much farther; his adherents went further after him. Known as the Dutchman, Erasmus was an intellect of unparalleled talent; his prodigious capacity for ancient languages helped not only mend textual mistakes of the Scripture of his day but helped revive the wisdom of the ancients with his collections of their insights. Erasmus had a profound impact on Luther, setting him, in some regard, on the path toward reform for which he is remembered. As often happens, the student surpassed the master. Whatever intellect Luther lacked, compared to Erasmus, he made up in clarity of vision and zeal. He saw a singular, apparent, unequivocal interruption to all scripture. The natural consequences of this dogma we feel today. The Adages was likely Erasmus's most commercially successful publication, which revived from the ancients and put into modern parlance such familiar phrases as “leaving no stone unturned,” “teaching an old dog new tricks,” or “breaking the ice.” Students today are more familiar with his satirical invective, In Praise of Folly, often seen as unleashing and making acceptable criticism of the universal Church. Erasmus pushed a disciplined approach to learning—some forms of his syllabus are still in effect among elite British schools today—to produce a classically trained individual whose conduct was right regardless of doctrine. To be clear, Erasmus was not pioneering in thinking here; he was reintroducing. His world already knew Aristotle. And Erasmus knew the Stagirite well, quoting him, even in repudiating some Parisian Scholastic’s abuses or misattributions. Only two decades after Erasmus's death did the medieval world receive a Latin translation of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. Massing does not make the connection, but arguably, Erasmus followed the lineage of Thomas Aquinas, who received the wisdom of Aristotle, paving the way for the reintroduction of Marcus Aurelius’ Mediations to the West – twenty years after the Dutchman’s death. This patrimony of thought might be justified for the foundation of Western humanism, given that this lineage grew without directly antagonizing Rome. This thinking flourished for centuries when Erasmus was largely ignored and forgotten. Massing’s Luther puts Paul—regardless of his authenticity or authority—as the central voice of Scripture and concludes that justification by faith alone is sufficient for man’s salvation. Coupled with a more Jansenist view of Original Sin, negating the concept of free will in favor of bondage, Luther envisioned a world where a man was incapable of redemption by personal conduct. Much, if not most, of the fight between these two, originates in conflicts over the text of the now-understood Bible. Erasmus was a translator extraordinaire. He uncovered many textual corruptions and their correlating misapplication or conclusion in doctrine. This put him at odds with the prevailing orthodoxy of his day. He cautioned against dogmas that might rely too heavily upon a “drowsy scribe” from the distant past. Erasmus published a “critical” edition of the New Testament, compiling all known translations in a side-by-side column comparison with his added annotations. This staggering work of scholastic achievement was meant to show that the received text had been corrupted in many places and did not represent the plainer spoken and popular speech the Apostles would have used. Aside from the theological and academic discourses that unfolded between these two subjects during their lifetime, this gave way to physical violence that lasted for centuries, fueled partly by the rise of the printing press. The physical atrocities inflicted during the Protestant uprising are so graphic as to be hardly imaginable to a modern reader. An example of the sheer bloodshed is one day in Alsace. When peasant defenders took refuge in a Church from Protestant rebels, they were burned out. Rushing outside, pleading for mercy, they were cut down; estimates of this slaughter range from two to six thousand. “Children as young as eight, ten, and twelve were killed; women and girls dragged through the cornfields, raped and murdered.” Luther did not condone this violence. He encouraged, approved, and exhorted the violence it took to subdue the anti-Catholic rebellion. He first noted his disapproval of the rebellion itself, noting: “For Luther, the peasants were blurring the lines between the two kingdoms—a crime far greater than any the princes had committed. The very idea of the peasants taking action to right wrongs enraged him. It was Christ’s desire that we not resist evil or injustice but yield and suffer. Romans, Corinthians, and Matthew all teach that Christians should suffer wrongs committed against them and love their prosecutors and enemies.” As the violence mounted, so did Luther’s passion against the rebels. In his tract, “Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants,” he wrote: “There, let everyone who can smite, slay and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful nor devilish than a rebel. IT is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him, he will strike you and the whole land with you.” Luther encouraged rulers to offer terms to the rebels and, if refused, to follow Romans 13 and “swiftly take to the sword.” There should be, he urged, “no patience or mercy. This is the time of the sword, not the day of grace.” To a modern reader, this might be disturbing. Still, Luther insisted that those in authority had an absolute duty to use equal or greater force in subduing and crushing the uprising. On these affairs, Luthor displayed a near masochist fetish for implementing an authoritarian state, making common conceptions of Machiavelli look sheepish. As Christendom split, it did not end the culture of persecution. Targets and forms morphed: Protestants persecuted other Protestants; Protestants persecuted Catholics; Catholics persecuted Protestants; and both persecuted the Jews. Believers and non-believers were beheaded for crimes of thought. The old order was torn asunder, and churches were razed, desecrated, and ransacked. New political orders – particularly in Europe’s north – aligned not so much upon issues of faith but opportunities of fortune. Luther stridently believed that the Christian’s life here on earth was subject to earthy constructs of secular power (render unto Creaser what Caesar’s). So, earthly princes had an absolute mandate and duty to provide, above all else, the foundation for all physical security: order. Order is maintained, then as now, by not suffering acts of rebellion. The majority of the time since his death, the Holy Roman Empire, to which he was devoted and attempted to correct, banished him. All of Erasmus's works, every book and article, remained for 400 years on the Pope’s forbidden book list. Ironic, given that a Pope at the time sought his help refuting the lowly monk in Wittenberg. Luther, the son of a miner, pursued monasticism in earnest. His guilt was never fully escapable. Prodigious in writing, he was never as scholastically talented as his sparring partner from the Netherlands. However, hatching the egg Erasmus laid, Luther translated the Bible into German, leading to the entire Protestant proliferation. While they never met, Luther, once inspired by Erasmus, turned from admiration to loathing. Their debates lasted until each of their deaths. The fault lines between debate, civility, and reform as a juxtaposition to dogmatic, uncompromising, angry, and invective will remind today’s reader of times strikingly familiar. The conflict of style will seem relevant, even if the relevance of the content of the debate has long faded. Massing’s work is wonderfully written, with creative, vivid, and passionate prose. It was, no doubt, a labor of aficion for its author. For anyone interested in the history of ideas, Christianity, the development of Western Civilization, or seeing from afar today, Fatal Discord is worth the effort. The dueling notions of humanity’s striving for better conduct versus man's natural and unrelenting depravity remain with us today. Did this fault line start with Erasmus and Luther, as Massing suggests? His work provides some clues but lacks clear and compelling evidence for a final verdict as such a complex question demands. Comments are closed.

|

NEWSLETTER SIGNUP

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed